My Phelim was a

chime child, born on the stroke of midnight, a miracle of all sorts. My seventh

son as well, a favourite of the Fair Folk some said, and I kept an eye on him

from his birth day, watching him when he mounted a fairy mound or skirted the

edge of the wild woods tangled around our pasture. He was a solemn child and a

silent one; when he emerged red and shining into the world I asked the midwife

if he was ill. I had never had a child so silent come into the world, nor one

that did not twist in the goodwife’s arms. Searched for blue lips, a blue face, the signs of

strangulation in my son but I saw only his dark small lashes, thin as black

thread, curled atop swelling cheeks. His breathing was hushed as the sea on a

windless day.

He continued to

be quiet. He spoke few words growing, and while I understood, for the few words

he spoke were always more important than the many words my other sons and my

husband ever spoke, my husband found it disconcerting. I did nothing to assuage

his worries when I impressed upon him that it was a good thing that Phelim

could get by one one word where everyone else needed five. Silence was not for

this life, my husband said. Silence was for the grave. And to mimic the grave

whilst alive beneath the sun was a mockery of life. He tried to coax sound from

Phelim with threats, and when Phelim did not yield, with the birch switch. Each

slap of the switch against Phelim’s back had me biting my tongue. I could not

bear to hear it but it felt like betrayal to retreat to the garden. So I

listened from the other room. I had heard the switch before, against my other

children, but when my husband beat them their cries drowned it all. This was a lone

sound, a slice in skin and in the silence, a bloody pendulum. A sound like

earth splitting, the chaotic pulse of the ocean. When it was done I heard

Phelim climb to his feet unsteadily, like a foal with spindly legs, but there

was never a sob to hear.

Phelim continued

his chores while the blood dried on his back and let me wash it away with cold

water and said nothing but to thank me and apologize for the ruination of

another shirt. He apologized for my husband as well, though my husband was

never there to see it. He was a birch switch himself, a thin sapling, a bone

whittled soft and smooth by time, pliant and unbreakable. It was not hard to

love Phelim for that, except that my love was hand in hand with my fear for

him. But fear strengthens love as much as it hardens the task. And it was

nothing to my pride.

They came late

on a summer night. When one day was tipping into the next, a tumble of stars

wheeling above our wheat and the drapery of the woods. The sort of day had

passed in which the sky was blue as cornflower, the air crisp with the scent of

apples and grass seed. It bled into a night sleepy with birdsong and warm with

firelight. There are always lanterns on the farm and in the garden on summer

nights. My boys had always stayed up late in the summer, unless a sharp word

from my husband has sent them to bed. But there were no sharp words for any of

them this night but Phelim. It neared midnight and he was inside with my

husband and the birch switch. I was alone in spotting the first of them, though

I did not know who they were at first. Now that I recall it, how could I have

mistaken them for an ordinary band of knights? Who else has steeds the colour

of smoke, with manes dark as the soil in the bottom of a river? Who else wears

armour black as laquered ebony, or cloaks the colour of silver ferns? Who else,

in the heat, would drape beech white caparisons upon their horses’ flanks and

who wore, fastened to their coats, bronze pins twisted in such mesmerizing

shapes? Who else blinked with eyes of different hues, one eye a dark deep

brown, like the shadows of the woods, and another like moonlight on the surface

of water?

The procession

came from the woods, though I had not heard them until they appeared at the

edge of our fields and flowed toward us. They did flow, a river of them,

rippling horse muscle and heavy cloaks. They were mostly men, and my sons, who

would normally had pressed their chests forward and their shoulders back,

tilted their chins up at though they could look down upon men on horseback, did

nearly shrink back. They could sense the arcane and wilderness in these men.

And it was not until one of them looked directly at my sons that I did realize

what riders were approaching our cottage. I would not dare hold my arms up in

front of my children. I would not dare challenge the Hunt before they had

spoken.

One rode ahead

of the rest, in an evergreen cloak that bled over the flanks of his monstrous,

jet horse. The horse was pressed against others, but no horse rode abreast of

him. They danced in restlessness as they slowed, and in the horses’ sweat I

could see muscles that spoke of days of racing, or nights of racing. The

green-clad knight was straight as though he were a tree erected in the saddle-

so proud! His features- sharper than any knife blade. His mouth was a cruel

line cut in his pale face, set with both amusement and the weight of great age,

a face that was a warning as much as it was intrigue. His hounds snapped at his

feet, at the horses’ hooves, but he paid them no mind. They were silent docks,

though their teeth struck against one another with a sound like flint against

stone. I was drawn to them all, these knights, at once. It is easy to be drawn

to the Fair Folk. It is easy to mistake their beauty for sugar, but monsters often

wear beautiful faces. I was weary and foolishly enchanted at once. I was glad

my husband was indoors so he would not see my flushed cheeks and twisting

fingers.

If Phelim had

been outside he would not have spoken a word. He would have let his silence

bring this conversation into neutral ground. He would had stood upon this land

and told the Fair Folk with only his glance whose it was. My son Noein leapt to

the ground beside me just before the knights were close enough to heard and

whispered furiously in my ear, voice a well of admiration and apprehension.

Should we get them wine, mother? Will their horses want water?

I meant to shake

my head, but had to consider the questions carefully. It would not do to refuse

the knights anything, but they had asked for nothing as of yet. We had no wine

fit for them, and their taste in wine was probably more than any human could

offer. We had only the wine we bought from a neighbour, dark as a seed deep in

the soil, dark as shade, but not enough to tempt the knights, surely. They were

used to drink that I could not imagine, and I was nothing but an initiate in

the ways of conversing with them. I could not begin to think of how to explain

that I did not have wine fir for them. I considered sending Noein inside to retrieve

some, so that I might explain it better, but the pulse of the birch switch

against Phelim’s back in the house distracted me. It might not be clear what

was happening, for Phelim was, as always, silent, but my husband did make up

for it. No more than a few seconds at a time passed without a shout, a jeer, or

insults that made the night more jagged than birdsong did. I heard only some of

it, but it was enough to make me flush anew in front of the strangers. Did

Phelim think he was worth the salt on the table? Did he think his flesh any

more valuable than the swine on our plates? He had another’s eyes, not his, and

a body too frail and thin to work the land properly. A disappointment, Phelim

had been, since he’d been born that night so many years ago.

Shame filled my

throat with heat as the shadow of the black horse descended on my garden. There

was no gate to the garden, only a gap in the fence, though the knights did not

come through it. Of course the knights could hear what was passing inside, but

they said nothing of it. Their black and silver eyes were fixed upon myself and

my children.

“Madam,” said

the green-clad knight in a voice as clear and cold as water. His face was dark

and even more sharply cut by the light of the lanterns. He looked like a god, a

creature born of the fire and the forest atop a steed as dark as rock. His gaze

made me shiver. “I have a thirst, as do my men. And our steeds. We will take

any water you have, if you have some to spare?”

I did not

believe it wise to be inhospitable and I did not believe in it, moreover. I

treated them as I would have any guests. I did not have to tell my children to

mind their tongues, though I wished I had taught them to mind their stares. I

was astonished none of them choked on flies as they gaped. Once their maws were

shut and my daughters were ushered out of the way, though they did not stop

gazing at the men, we watered the horses and watered the knights. The hands the

took the drinks were young and graceful, as fluid as water themselves. They

were not the hands of those that handled timbre or rock or churned dirt. There

were calluses upon their palms from gripping reigns, and red strikes across

their fingers where they had twisted their fingers too tightly in the manes of

their steeds. They looked shaped around the riding of these horses. The knights

looked grateful for the water, young and easy as my boys. They requested water

for their hounds too, and though their hounds were silent they snapped their

jaws warningly as my boys came forth with water and left it at the horses’

hooves for the hounds to drink.

The green-clad

knight did not thank me but he did look satisfied. He tapped his belt as though

he would produce a coin from it, from one of the pockets of his tunic. Instead,

he said, “Our hounds are restless and easily distracted. And they have grown in

number. I need someone to tend them for the next year before the winter weeds

them out and returns them to a manageable number. Would you be able to spare

one of your sons, Madam, for the task? I should return him again, when we ride

back in the summer.”

I said nothing

at first. I had given him water and it was not enough? I would rather have

given him all of our wine and water. But how to refuse these knights and this

man? I did not think his hounds would tolerate it if I refused him. These

knights were not known for their benevolence. They did not move as midnight

stretched around us. “I do not know how I can spare one of my sons, sir. Not

with the harvest approaching. My daughters can not do all of the work. And I am

not sure you would want one of them.”

It was too much.

I snapped my mouth closed as soon as I had finished speaking. I had not meant

to say so much, but it was too late. I had challenged them. They did not look

challenged as their gazes wandered. The green-clad knight’s eyes lifted to the window

beside our front door, as though he could see through our curtains. There was

ice in his black and silver eyes. “Daughters speak more than sons. Sons often

speak too much anyway. A quiet son, I would take. The hounds prefer the quiet.

He would have no trouble at all.” He looked down upon me again. “Have you a

quiet son?”

It was an offer

to take my son. Both an offer and a demand. He could hear the birch switch as

clearly as I could. When Phelim did appear outside and ask quietly what hounds

were baying it was quite clear that he was to go with them.

I have known

sorrow, but there is very little that compares to missing one’s children. And

Phelim, my silent child, my precious child, my chime child, I missed him

dearly. I wished to see the knights descending out of the forest again when the

trees bled yellow and scarlet over the horizon, when the frost climbed the

windowpanes and the snow feathered the frozen soil and the trees on the roadside.

I wanted to smell horses in the air when spring arrived, but I only smelled the

carcasses of animals that had died and frozen in the winter, thawing, and the

green, growing scent of buds and blossoming brambles, and the musk of frisky

animals. I missed his silence when I heard my other sons cry beneath my

husband’s birch switch. I thought perhaps, in the summer, when he returned, it

was their cries that had brought him back to us.

There were fewer

hounds this time, as the green-clad rider had said there would be, and the same

number of knights, though this time my Phelim had joined their number, atop his

own black steed, dressed no less resplendently. He trailed after the green-clad

rider, who stopped at our fence and did not cross the threshold but smiled with

cold generosity at myself and my children. It was much too late to be calling,

to be returning my son to me, but I would accept him at midnight or midday. “I

did say I would return him, did I not, Madam?” the green-clad rider said. “Your

son has been as silent as I have needed him to be. I would say that his time

with us had sharpened that silence. If you find his quiet refined do not be

alarmed.”

He gestured, and

Phelim dismounted and strode toward us through the line of horses. My sapling

boy had become a tree, lean but strong as a birch tree. In that year he had

changed remarkably. I knew he had changed in more ways than that when I looked

into his face and saw his eyes.

But I could not

slight the knights. No matter how the sight of my Phelim frightened me now. “I

am glad you returned him, sir. Thank you for doing so,” I said.

“You are

welcome,” the rider said, and began to turn his horse away. He paused on the

other side of the fence and turned back to Phelim. Phelim looked up at him, as

though the rider had called, though he had not. The armour of the rider’s

shoulder reflected light into his sharp face. “Remember what I said. Remember

where you have been,” the rider said to Phelim. Phelim said nothing and though

he was quiet, I was surprised. It was rude not to answer. But the rider did not

look offended; perhaps it was he that had taught Phelim to become even more

silent. Then the knight looked into the window of my husband’s cottage, as he

had the year before, as though he could see my husband in the window. “Farewell,

Madam. Good night.”

Then they

departed. The hounds gnashed their teeth once more in my direction,

soundlessly, though Phelim looked down upon them. When he did, they set their

jaws and bounded after their masters. In a few moments the knights had vanished

into the forest and there was nothing there to say that they had come and gone

at all. Nothing but my new son, looking up at the sky as though there were

something to see in it. He was quiet as the grave as we went indoors, as he

took off his cloak, as he unstrapped the light armour around his shoulders. He

was silent as he looked as my husband with his new black and silver eyes and

when midnight struck he pulled a dagger from his belt and slit my husband open

from neck to navel. My husband was silent as he fell across the dinner table.

Phelim wiped the blade on the tablecloth as I wiped tears from my eyes and said

not a word.

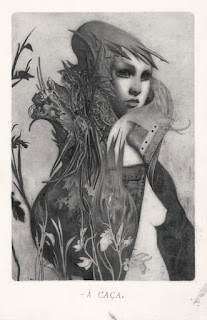

Art by Joao Ruas

Text by Lucie MacAulay

No comments:

Post a Comment