The beach was

full, an odd sight; not because there was never anyone on it, but because it

was the dead of night, so dark that it was difficult to tell the black water

apart from the black sky, since they were both dusted with stars and filled

with the tinsel-silver light of the moon.

Someone had

taken care to set up lanterns closer to the shore, determined flames in wicker

and plastic lamps stuck to poles dug deep into the sand. Their light carved

rosy haloes out of the darkness. There were more lanterns in the festival,

strung up between the noisy stalls on the boardwalk. Nimue walked just beside

the boardwalk, where she could smell the sea, where the water was no more than

twenty feet from her. She’d never thought the sea smelled like salt and tonight

it smelled almost wintery with its freshness, as though the dark pulled from it

every summery note.

There were

several silhouettes on the beach, dancing in front of the lanterns. A few

couples were walking in the surf, their shoes dangling from their hands. Nimue

had abandoned her own shoes long ago and tucked them into her mother’s bag

while she walked. She’d left Tristram to debate whether or not taking off his

shoes was worth it, and then to argue with their mother about how wise it was

to remove one’s shoes if one were staying on the boardwalk. No one had broken a

bottle on it yet, Nimue noticed. But she hadn’t wanted to be a part of their

argument.

None of the

silhouettes were familiar. Nimue almost didn’t notice the ones approaching her

until they were only a couple yards away, and then she wondered how she could

have missed them. She wondered for a moment, with some dread, if someone from

school had recognized her alone in the festival. But it was no one she knew; a

band of five people stood before her, and as soon as they realized they had her

attention, they began to dance and sing. Nimue was so shocked and stunned by

the abruptness of their routine that she did not realize for a moment that it

was not all of them singing at once, only two of them, or three. The resonance

in their voices sounded like the hiss of the sea, though she couldn’t remember

if it had been that loud a moment ago. She recognized none of their words, but

the song was arcane, lulling, and oddly hungry. Their dance was odd to watch

and would have been embarrassing if she did not see the ripple of muscle in the

lantern-light. They leapt over the sand, trailing it from their toes, from the

folds of their clothing.

“The hell?”

Tristram’s bare feet pounded on the boardwalk. He dropped into the sand,

fumbling with the laces of his sneakers, twisted together in his fingers. He

wobbled unsteadily as he strode toward his sister. “You said you were going to

look for a drink. Of course you’re down by the water- what?”

“Dancers,” Nimue

said, as though Tristram weren’t staring at them.

“Really,”

Tristram said. The look he turned on the performers was at once inviting and

dismissive. Their mother often said Tristram could charm the birds out of

trees, and it was apparent in every feature of his face, in the wide smile and

his fine-boned nose as he tilted his head down. He had laughing eyes, bright

and amused, though one couldn’t be sure, looking at him, if they had done

something to amuse him, or if he had found his own amusement outside of present

company. He swept his gaze over the dancers and his smile widened. One of the

dancers, a singer, Nimue thought, watching her lips move, glanced at Tristram’s

smile and returned it, with several degrees more warmth. But she did not cease

her singing. Their voices were less the hiss of the ocean and more a swell,

rising and falling together as though buoyed on a wave. Tristram leaned forward

and spoke lowly in Nimue’s ear. She almost leaned away from him; he smelled of

cider and his whisper was cold and pointed as an icicle. “Are they homeless? Do

they want money or something?”

Nimue did not

think it was money that they were after.

Tristram moved

Nimue and himself further from the boardwalk, or at least turned them against

the stares of anyone who might notice that they stood before a band of nimble

but disorganized dancers. They were a little closer to the sea and, as if the

sea were climbing the shore toward them, Nimue smelled sand and waterweed and

the nearly bloody scent of water. Nimue could still smell cinnamon doughnuts

and ginger cake and lemon tea from the boardwalk. Tristram had one hand holding

his other elbow, his shoes still dangling by his side, though he was swinging

them almost rhythmically, though Nimue didn’t think the song the performers

sang had a rhythm. Nothing consistent, anyway. It seemed to skip and flow, as

though they sang around rocks.

Something

fluttered at their feet. Nimue let herself look at it for a moment and

realized, with some surprise, that it was a fox. Though she wasn’t sure she’d

ever seen a fox that colour, starry white and mottled with grey like the skin

of a seal. She stared at it hard, trying to figure out if it had been there

before. Its paws were dug deep into the sand, as though the beach had shifted

around it. It returned her look with a hint of cleverness and tilted its head

as though to tell her listen. The song’s

not over.

Nimue nudged

Tristram to try to point to the fox, but he knocked her hand aside and

continued to gave politely at the dancers. He looked away once, to the watch on

his wrist. It was an hour behind but it told Nimue that she had been listening

to the song for nearly twenty minutes. She frowned, aware that the performers

could see it. She hadn’t realized she’d been listening that long.

The song began

to wind down. Nimue was not sure how she knew, only the it was like a rolling

tide slowing and gentling. When it finally came to an end it seemed to linger

like salt spray. Tristram nodded and clapped his free hand against his leg in

an approximation of applause. “Nice. That was great.”

One of the

dancers, a fair-skinned and raven-haired man so tall that he seemed to bend

forward out of habit of speaking to everyone shorter than him, leaned forward

and blinked silky black eyes at them. “Thank you. That’s kind.”

“I’ve never seen

a dance like that before,” Tristram said. If anyone else had said it, it might

have sounded like an invitation to share. When Tristram said it it was a polite

and detached observation.

The black-haired

man turned to Nimue. The fox in the sand turned with him. The performers

assembled in front of Tristram and Nimue like carolers. “I would like to know

what you think, love. Did you enjoy it? Did it please you?”

Nimue folded her

arms over her chest, felt the uncomfortable stickiness of her skin in the

summer heat, and dropped them again. “I don’t really like the share the things

that please me with complete strangers.”

Tristram’s elbow

was sharp in her ribs. He hissed, “Nimue.”

The black-haired

dancer did not look offended, though. He smiled, his dark lips stretched

widely. He tilted his head at her, as though she had won something. Nimue tried

to recall if he’d been one of the ones singing, but she couldn’t. “That is your

right, Nimue.” When he said her name a shiver rolled over her shoulders, as

though someone trailed icy fingertips from one shoulder blade to the other. The

dancer’s gave drifted from Nimue to the woman beside him. She was older than

Tristram, though only just, with raggedly cut hair and hawthorn-berry lips.

There were flowers strung through her hair, white, like narcissus, though Nimue

didn’t think narcissus grew anywhere near them. They hung on dark green strands,

like dried waterweed. The woman looked back at him for only a second, but the

fox trotted closer to them. It turned an identical gave on Nimue.

Tristram was

patting his pockets, as though he’d only just remembered what he’d told Nimue and

realized that because the dancers had performed for them only, he had to offer

them something. “I don’t have any change on me,” he said. “I mean, if I found

our mum I could buy you all a drink or something. There’s cider and ale.

There’s a good pint back down the boardwalk. But you performed for the wrong

people. We don’t carry anything in our pockets.”

“We’d accept

another singer,” said one of the dancers. She had definitely been a singer. She

had a face wizened as an old rose bush. Her hands moved lightly through the

air. Her hair drifted and slipped over her shoulders. She was wearing a wispy

white shirt, one that looked like the sort of thing Nimue’s grandmother might

wear, but it was sprayed with salt. The wet patches were just visible in the

lantern light where they clung to her arms and ribs. Nimue saw that her nails

were softened as beach glass, glittering as if with sugar. “We’ve been losing

singers for some time. Dancers we’d also accept, but we need voices with us.”

The fox bowed

its head and looked for a moment as though it might burrow its head into the

sand. Then it leapt on something in the sand, though Nimue hadn’t seen anything

move. The performers looked sad and fierce, like a band of knights afore a

cave. But the darkness was behind them, the dark ocean heaving in the dark sky.

Nimue wondered how many of them there had been to start, of it there had been a

start. If they’d been shedding some of their number and making them back so

long they could not know themselves where they started.

Tristram opened

his mouth and Nimue could tell he was about to say something that would reveal

how absurd he found the request, how he believed, truly, that they were joking.

So before he could, she said, “You’re not from around here, are you? And you’re

not travelling by car?”

Tristram tapped

Nimue’s elbow and almost scowled. “Don’t be stupid. They didn’t walk here if

they’re from out the city. They’re not travelling on foot.”

“They could, if

they don’t have too much luggage,” Nimue said.

The black-haired

performer raised a brow and turned. The other performers stepped aside and

pointed down the beach, where there was another silhouette on the sand, closer

to the surf than the boardwalk, undisturbed and black against the lantern

light. There was a sled resting atop the sand, a collection of suitcases on it.

They looked as though, full, they would be too heavy for a single person to

cart across the sand, even on a sled. But there was only one figure at the hind

of the sled, hands curled around the sled’s handles. He was turned forward,

away from them, but there was a stillness about him that spoke to Nimue of

intent.

Nimue’s stomach

twisted and flipped as she tried to look more closely at the shadowed face,

then looked at the shape and length of the fingers on the sled instead.

“You really are

hitchhiking, huh?” Tristram said. “Christ, that’s bold. What about in the

winter? It’s the summer and the nights get cold anyway. How can you dance, or

even travel?”

“Tonight is the

shortest night of the year,” said the blonde dancer with hawthorn lips.

Tristram looked to her instantly, taking in the soft angles of her face and icy

beauty, but the dancer was looking at Nimue when she spoke.

“Obviously,”

Nimue said, watching the figure at the sled. The figure didn’t look at her, but

Nimue thought she saw the slightest tilt of the figure’s shoulders, as though

she had been heard. She wanted the figure to know that she knew what night it

was, that she knew a lot.

“Look, if you

wait a minute, I’ll bring my mum over, honestly,” Tristram said. “She didn’t

see your dance but she’s got our money on her. I’ll buy you a round if you

want. Or something to eat. Maybe you can sing again for her, yeah? She’s just a

little bit back on the walk. She’d be totally- wait just a minute.”

Tristram turned

and trudged up the sand, leaping onto the boardwalk. He didn’t bother to put

his shoes back on but walked on the worn wood. The boardwalk was loud, but as

though he’d closed a door between the beach and the boardwalk, it was quiet on

the sand. Nimue could hear the sea breathing on the edge of the sand. They

hadn’t gotten closer to the sea, but it seemed louder anyway. The black-haired

dancer’s eyes followed Tristram away, then returned to Nimue when the crowd had

closed in on her brother.

“Will you sing

with us, then?” he asked. “Or dance? I think you’d prefer to sing, though.”

“That’s quite an

assumption,” Nimue said. “I don’t want you to ask me-” She nodded at the figure

behind the sled. “I want him to ask me.”

The performers turned

back again to the silent one holding their belongings. The figure reminded

Nimue almost of the ferryman that brought souls across the river of the

underworld. She saw now that the white and grey fox at the performers’ feet was

not the only one. There were a couple more on the sleigh, though their fur was

wet, plastered to them like a pelt. Their black eyes flashed as they turned

toward and away from the lanterns.

“He won’t speak

to you,” the older singer said. There was a huskiness in her voice as though

she did not have the energy for anger. “That isn’t his purpose. He is here to

bring us where we need to go, that’s all.”

“Where is that?”

Nimue asked. “To my brother and I? To me? What for?”

One of the

singer’s looked taken aback, but the black-haired dancer spoke calmly. “We did

not choose you, exactly. We ask every one for a singer. We go up and down the

water to ask. We try to collect singers and dancers. Every summer. We dance. We

sing-”

“We have to go

back before the winters freezes everything over,” the blonde dancer said. Nimue

wasn’t sure that the dancer was worried about “everything”, but she didn’t ask

what the dancer really was worried about, or if it had anything to do with her.

“I know you,”

Nimue said, speaking from a memory. “I remember you last summer. You came to

the docks and sang. My dad was on his boat. He heard you.” They didn’t ask

after her father, and she didn’t tell them who he was. “You had more then. And

it wasn’t you. Different singers and dancers, but it was your kind, wasn’t it?”

“Your kind” didn’t seem polite, but the performers were noble and unbothered by

it.

On the

boardwalk, as though sound were bleeding through the invisible door between the

festival and the beach, Nimue’s mother sounded annoyed and as though she were

fighting Tristram, who was probably pulling her down the boardwalk. The figure

behind the sled slid his hands back so the heel of his hands were nearly

pushing against the handles. He tapped a finger once. Nimue saw it, though she

did not hear it.

The performers

did not see it. The elderly dancer nodded at Nimue. “We are using up the night.

There is only so much of it left. We need to leave now. Are you coming to sing

with us?”

“Are you going

to bring me back?” Nimue said.

“At the end of

the night, maybe,” said the black-haired man. He exchanged a look with the fox,

who looked judging and hard. “Maybe in the winter. Maybe next summer.”

“Maybe next

summer,” Nimue echoed.

Tristram was

almost upon them, with their mother. Their mother sounded aggrieved to have

been pulled this far along the boardwalk, and more aggrieved to be led toward

the sand. “I did not agree to talking my shoes off. Tristram- Tristram! I’d

rather you were getting drunk with your friends if you’re going to spend the

night dragging me hither and-”

“Do you really

need me?” Nimue asked.

“I don’t think I

should share with a complete stranger what I do or do not need,” the

black-haired man said.

Nimue almost

appreciated his words. It made the thrumming in her hands lessen, but she could

not stop from fidgeting with the bangles on her wrist. “Next summer, really?”

The figure on

the beach gave the sled a push. It moved a few inches across the sand, not far

at all, but enough to send a jolt through Nimue’s chest. The performers took a

step back across the sand. Nimue thought maybe the figure had heard the

hesitation in her words and wished that he hadn’t. She wished he would give her

another minute, but he moved the sled another couple of inches. The ocean

suddenly seemed hungry behind him.

“It might be,”

the black-haired dancer said, gently. But no one looked as though they believed

him.

“You’ve only

just asked me,” Nimue said, frantic and angry at her jitteryness. The

performers were moving across the sand toward the sled, with much more

organization than they had danced with. The lanterns on the shore rendered then

like ink. The ocean heaved onto the shore.

“And now you

have just to decide,” one of the dancers called back. Nimue could not tell

which it was, and she was distracted from trying to deduce who it was by the

fox throwing itself toward the shore. It cleared the front of the sled, then

turned abruptly and sped back to it, as though something in the water had

spooked it, though Nimue saw nothing on the shore. The other foxes on the sled

moved restlessly, looking less like a nest and more like a tangled, shifting

knot. The sled’s driver whistled at them, clear and colourless as water, and

the foxes settled. The one that had raced toward the water still looked that

way, its ears pricked up in the warm wind.

Tristram pulled

his mother to the edge of the boardwalk and hopped into the sand. “Here, mum.”

“What did you

and Nimue want to show me?” Their mother asked.

Tristram and his

mother looked at the empty sand and the couples crowded around the lanterns on

the shore.

Tristram looked

up and down the length of the sea. “Nimue?”

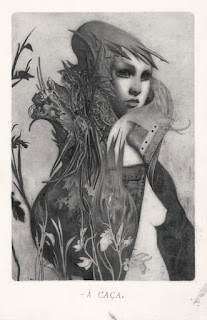

Art by Barbara Florczyk

Textby Lucie MacAulay