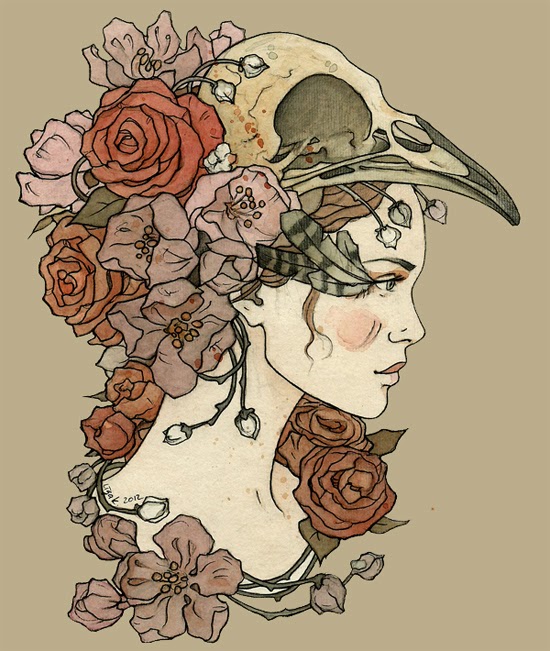

The crow girl

waits until the sun has just peeked over the horizon, yellows and reds chasing

away the azures and blacks of night, to leave. It will be an hour or two before

William is awake, though the knowledge does not impact her decision.

She could wake

him, could try to explain where she is going, but he can do nothing except

follow her and the thought of saying goodbye fills her with remorse.

She rises and

dresses quietly, careful not to disturb any other sleepers.

The crow girl

carefully folds the yellow scarf and places it on her pillow. She goes quietly

downstairs to the front door. She doesn’t put shoes on, nor the charcoal coat

hanging on the hook that was leant to her by William’s mother.

She takes

nothing with her as she leaves.

She closes the

door to the house as quietly as she is able, without hesitation. Perhaps if she

were like William, if she were like anyone in the village, she could remain and

live independently. And the red sun would return and eventually even the crows

would die from the heat.

Leaving is the

best gift she can think to give William in exchange for his kindness.

It is early

enough that there are only a few villagers awake and outdoors, to stare at the

girl with no boots who is never seen without William by her side.

She walks past

the bakeries she has come to recognize by the smells wafting from them, past

the school she has never attended, and the square where the boys stoned the

crow. She pays no attention to any of it, or to the villagers. It is as though

she is not walking through the village at all, but introspectively walking

through an entirely different landscape, blind to the buildings and people

around her.

At the edge of

the village she keeps walking.

She walks across

the field to the trees she and William have climbed several times. They are

full of crows, boughs bending under the weight of them. Then she continues

walking, into the farther fields, where William has never gone.

The better hours

of the morning have drifted by when the tower rises on the horizon. Still an

hour’s journey, but she can already see the crumbling reliefs around the top of

it, the way shadows cling to it like they cling to nothing else.

Her stride does

not change, she keeps a steady pace as she nears the tower, and though several

crows disappear within the window at the top of it, her eyes are trained on the

doorway at the bottom of it.

There is no

door, whatever hung on the blackened hinges on the wall is long gone. It is

simply a dark opening, as welcoming as the dark of night when one wakes from a

nightmare, and it is overrun with weeds and vines. The crow girl walks through

them. Burs stick to the hem of her skirt, nettles bite her feet, but she

vanishes into the darkness and does not emerge.

The crow queen

stands at the balcony, gazing over the field. Her view of the village is

obscured by trees, thick on the horizon, even leafless. But she has seen the

crow girl coming and knows when she is standing behind her.

The hollowness

in the crow queen’s chest pounds, as if her heart has returned.

She turns

slowly, unsure what exactly she will face as she does.

It is the crow

girl, standing as still as if she were made of the same stone as the tower. She

wears a white blouse and a grey skirt, but no shoes. She could be one of the

village children, curious and lost. But she is not. At the moment the space

they stand in is completely still, silent. No rustling of feathered wings. The

crows are frozen to their perches, motionless.

The queen stares

at the crow girl, into the eyes as dark as her own. They stand at opposite

sides of a cavernous room strewn with bones and rocks, glittering with

candlelight. A smudged chalk diagram decorates the floor between them.

“I did not call

you back,” the crow queen says. She offers no welcome, extends no hand of friendship

or niceties.

“It does not

matter,” the crow girl says.

“I banished

you,” the crow queen replies.

“It does not

matter.”

“I killed you,”

the crow queen says, her voice rising.

“No you didn’t. Sometimes

I need to grow again,” says the girl. “If I’ve been damaged enough. I was safe,

and now I’m not, and that’s the way it needs to be again.”

“Where did you

come from?” the crow queen demands, not in English, but in a language

understood by each bird in the room, who flap their wings and shuffle on their

perches in nervousness.

The girl does

not answer. She takes step after measured step toward the crow queen. “You can

give me away and protect me and hide me, but you cannot get rid of me. No one

can. I am essential.”

The crow queen

shakes her head. To her surprise, the girl smiles.

“Yes.”

The crow girl

holds up her hands, as if in prayer, looking into the crow queen’s black eyes.

“Let the dead be. Draw down the red sun.”

The crow queen

shakes her head. She is pale, and trembling. The crow girl does not seem to

notice either her response or her appearance. There is an intensity in her eyes

as though she were gazing not at the crow queen, but at the passage of time

belonging to the her, through her and into her past. And there is age in her

eyes, old age and weariness.

The crow girl

reaches up to touch the crow queen’s crown. It is a twist of thorns and vines

and dry twigs and string, and it is grander than any king’s crown. But the crow

girl will not bow to the woman-king. One does not bow to the thing they have

weakened.

Then she lifts

her hands and cups them, as if she were preparing to catch water or rain within

them. But what bursts from her fingers is not water. Fire appears, as if she

held a candle, but there is no candle or match in her hand. This is no illusion

or clever trick.

The first flames

lick at the girl’s fingers, held between them, as if the red sun that rose for

days is rising between them. Then they grow. They are as long and winding as

serpents, towering over the girl, in front of the queen.

The crow queen

wishes she could run away, forever avoid this moment and the consequences that

will follow it. Instead she watches as the flames burn white, like the centre

of a flame.

The light of the

fire is blinding, and the crow queen closes her eyes against it. The light

flashes red through her eyelids. She does not see the girl step forward, step into her, as easily as if she were

stepping into water.

Then there is

the pain. It is too sharp to comprehend, to stand. It is worse than the pain of

ripping out her own heart.

For a moment she

thinks perhaps she has been torn apart and stitched back together incorrectly. If

the crow queen could open her mouth, she would scream, and her cry would

frighten birds from their trees, would wake children from dreams.

Then there is

nothing. No fire. No girl. No agitated cawing. Nothing but a quiet timeless

stretch in which the surroundings slowly return.

She blinks,

staring at a white pattern of stars, smudged. It is a moment before she

realizes she is staring at the floor of the tower, surrounded by broken

candlesticks and extinguished candles. The in-billowing breeze, damp as though

it has just rained, is cool against her skin.

She rises to her

knees, then, slowly, to her feet. It is still morning. The sun is battling

through the mist, piercing it with golden spears, glittering on the dew-covered

grass. There is an entire village beyond the mist, and something in her aches

for it.

It is just

beginning to weigh on her now, the heaviness. There is an ache in her chest

that was not there before. But there is also something else, another feeling. She

cannot explain it but it settles around her as much as inside her. Broken

promises and disappointments, heartbreak, falls away. She feels more grounded

than she has in weeks.

The crow queen

presses her fingertips to her chest and, beneath them, feels the beat of her

heart.

Art by Liga Klavina

Text by Lucie MacAulay

No comments:

Post a Comment