In those days the

mist returns in the mornings, no longer driven away by the heat, lingering

about the trees and streets in the cool early hours.

The water in the

riverbed rises, consuming shiny rocks and turning the bank into a muddy mess.

The scarlet

recedes from the sky, and from the sun. It is less like a ruby today than it

has been since the first morning the sun rose like that.

The sun that

rises is milky gold, nearly silver in the mist, when William notices it.

The birds do not

return but William suspects that is large because it has become too cold for them.

Even the crows have begun to huddle together for warmth.

William and the

crow girl – that is the name he has given her, as she will have no other and

hasn’t one for herself – pass these days in the garden, helping his mother

organize the plants that withered in the heat. In the afternoons he takes her

around the village, acquainting her with the streets, traversing the paths that

loop behind banks and the school and bakeries back to the square, where he uses

his money to buy her hot chocolate. He watches her reaction when she has her

first sip and is relieved she seems delighted by it.

Occasionally

William sits in the room his mother calls the parlour, which is a small space

beside the kitchen, near the front door, and her reads, while the crow girl gazes

out the window.

The light

through the window is aureate, as golden as if it were midsummer. The crows

take to the spaces beneath awnings. To the balconies where the walls protect

them from the wind-directed rain.

William’s mother

drifts by, then stops, her attention caught by the crow girl. “What are you

doing?” she asks.

“Watching the

rain,” is her reply. When William’s mother glances out the window she sees a

clear blue sky and a sun that is only somewhat scarlet. There is not a cloud in

sight and no hint of rain. But she says nothing to her son’s strange friend.

It is an hour

later, when William has joined her at the window, that the rain starts. Huge

sheets of it that fill the gutters and sparkle on the windowsill.

There are

several days of rain following the first rainstorm. Raincoats and boots are

donned, umbrellas dot the streets, sheltering those who have braved the weather

or those who have appointments to keep.

William and the

crow girl make excursions around town at these times, to bookstores and the

library, avoiding the worst of it, though they do get caught in some of the

rain and return home looking as if they have climbed out of a river.

The rain becomes

a drizzle, light enough to venture out in without an umbrella, should one with,

which is how William and the crow girl spend an afternoon. They traverse the

shining rain-slicked cobblestones at a lazy pace, with no destination in mind.

Oftentimes they

end up in the cemetery, adding their own silence to the already-present

silence. The silence of the absence of mourners or passersby.

They walk past

rows and rows of graves, past names they do not recognize and some that have

been worn away by the wind and time.

William tries to

speak, to fill the quiet, but after his attempts at conversation are met by

short remarks that dissolve into thoughtful silences, he gives up. The crow

girl is clearly preoccupied. It is exactly a week after her arrival that he

discovers by what she is preoccupied.

They are leaning

against a tree, staring across the crest of a small hill dotted with graves. A

crow caws, ruffling its feathers. The carmine-coloured leaves quiver on their

branches. The dirt around the headstone trembles as if stirred by the smallest

wind, though William can see nothing.

When the crow girl

turns her head, quickly, like a cat, toward the source of the disquiet, William

follows her gaze. There is a figure standing over one of the graves, tall with

a dark suit, and a bowler hat.

And William

realizes, though it is difficult to see in the shadow, the man is completely

transparent. William can see other headstones and trees behind him, through

him.

The sunlight

catching the silhouette of him, in a black waist coat and pants. It highlights

the lines in his face, as there are no creases in his coat or the shirt beneath

it. His eyes are wells of shadow hovering in the air. And it is not only his

eyes, some way away William spots another pair of dark hollows, though these

are considerably lower than the first one and are not watching the nameless girl

as he stands and stares directly into the first apparition.

The crow girl is

still beside William, her gaze fixed as if she cannot bear to tear her eyes

away. She is not staring through the transparent man, but at him. At the glint

of watch half sunk into his breast pocket.

Her gaze

intensifies. The words cease. The shadow on the grave shudders like a candle

flame, and disappears.

The feeling of

unease felt by villagers in and around the cemetery slowly dissipates. It is no

longer a place for ghosts and crows. It is once more a place of respectful

silence and melancholy and peace.

Wherever she

goes, the crow girl is watched. There are at least one, if not a dozen, crows

following her about. They are outside the door when she and William depart in

the mornings, they fly from perch to perch hen she and William climb the trees

across the field, they wait at windows when she sleeps at night. She does not

find it disconcerting in the least. When William comments on it she only smiles

and insists she feels safer, as if she were among friends.

One afternoon,

William and the crow girl are enjoying their hot chocolate in the square,

holding the steaming cups in their hands, sipping it slowly, when a band of

children William only vaguely knows from school begins to seize rocks and throw

them at the crows lining one wall of the bank.

There is jeering

and laughter, loud enough to call the attention of William and the crow girl,

and several adults. The people passing by pay no attention to the cruel boys

stoning the crows; there are always more crows.

But the crow

girl sets down her cup, her hands shaking, visibly distressed. Then she grows.

It is an expression like the discovery of horror. William averts his eyes,

shuddering, and in a moment he hears silence in the square, as noticeable as if

the square were suddenly flooded with light, as cold as ice. The village boys

have ceased their merriment; have ceased their abusive rock-throwing game. They

are caught in the gaze of the crow girl, yet none of them can look her in the

eye.

Only one of them

looks marginally defiant and irritated that their game has been disrupted, as

they depart, but they are all anxious to leave, clearly uncomfortable under the

scrutiny and cold glare of the bone-white girl with black eyes.

William and the

crow girl find other ways to amuse themselves, especially with the improving

weather.

They spend hours

exploring the field outside the village, seeing how far it stretches in any

direction. They find interesting beetles, iridescent like green silk,

unfamiliar stones that, upon further investigation, they recognize as quartz.

The crow girl reveals nothing about her parents or family. She insists she has

nothing to say, with such honesty and so often that William feels perhaps she

really does not have parents, or otherwise does not know. But he does not pry,

instead asking her if she has enjoyed her time with him – in the village. She

replies that she has, and the smile that accompanies this statement is so warm

William cannot keep himself from grinning.

Best of all, she

will climb with him to the tops of trees. They ascend several trees in fields

and orchards, William hovers a branch above her, or when there is enough space,

they sit next to one another, like two nesting ravens.

They see views

of the town that William has only ever seen alone. He often finds he is nervous

when they climb together, afraid she will not enjoy sharing the view with him

as much as he does. That she will be impressed, but will not see the beauty of

it.

But she seems

overjoyed to be so high. She is sharpest, more immediate and content, in the

treetops. Sh says nothing about he branches swaying around them, expression no

concerns about falling.

Once, they climb

to the top of the tree that William found her egg in. He hasn’t climbed it

since that day, but the branches and knots are familiar. He grasps for foot

holds and hand holds with ease.

One day they sit

on the low branches, to watch the sun rise from over the tall grasses of the

field, rather than the low hills. In the lull of the ending day, of the

coolness and the quiet, and the stirring of the dead leaves around their feet,

which dangle off the branches, William broaches the subject of her arrival.

“Most people don’t come from eggs,” he informs her.

The crow girl

smiles. “I know. But it was the only way.”

William wonders

what she means by that, but decides against asking. “Why are you here?” He does

not mean to sound rude, he is simply curious as to what twists of fate brought

her to this village, to his tree and this nest, or if she would have been

hatched in another nest at all.

“I have to

mend,” she says cryptically.

“Why? What

happened?”

“What always

happens. To everyone’s. Some people deal with it differently than others. But

when I’m mended I’ll go back, because everyone needs one.”

She does not

elaborate. These are the mysterious declarations William has come to expect

from her, though it does not make it easier to comprehend. And he is distracted

now, by the mention of her leaving. He does not know where she will go back to, but he does not care. This is

the first moment he contemplated the idea that she would not stay, would not be

there to climb tree with him in the spring, or the next summer, or a year or

several years from now.

The silence

between them stretches. He cannot stand it. “I’ve never seen someone hatched

from an egg,” William admits.

“I’ve never seen

someone climb as high as you do,” says the crow girl with a smile.

William feels

colour rise in his cheeks. “You’ve never seen anyone climb at all, except for

me,” he points out, be he is inexplicably pleased.

He has been

feeling more content since the heat vanished, though it has more to do with the

drop in temperature.

The village

smells as it does each autumn, of woodsmoke and the first cool crisp winds of

winter, and of the cinnamon pastries in the bakery, and the damp earth. The

strange feeling has disappeared. The feeling like a clock not quite oscillating

properly, of scales being tipped too much on each side. Were the village a

clock with would be polished and ticking steadily, almost in perfect condition.

Though William also has the impression that the hands of the clocks, the

measures of minutes and seconds, are converging toward an event. A something that will soon take place. And

he cannot tell where it will lead.

The crow girl

has made an impression on her environment, as much as she has on William. He

has learned small things about her from sharing meals, sitting next to one

another in the evenings.

She does not

drink tea at all, and will only read by candlelight.

She will not

sleep before midnight but wakes before William’s parents are up.

She remembers

the faces of everyone in the village, even if she does not recall their names.

And there are

indications of her in every room of the house, as if she has lived their all

her life. The walls themselves radiate an impression of her quiet and

calculating demeanor.

Her room has

begun to smell of honey and cream and something like wild sage. It permeates

the yellow wool scarf William’s mother lends her, though the girl does not seem

to get cold.

The room is

untouched in certain corners, but a glance at the bed is enough to warrant a

second look.

The bed is a

nest of oddities and rubbish that Williams’ parents regard with uncertainty,

hesitant to relay morays of cleanliness to their guest. In the twisted up

sheets of her bed are an assortment of twigs wrapped with loose bits of string,

several black feathers-strangely undamaged despite having been slept on. An

entire raven’s wing that she and William found in the field one day. A shiny

black rock that William’s mother identified as onyx. A candle that William’s

father gave her to read by before bed, though it was half run down and now

remains unlit, nestles in the folds of linen sheets. And recently, mounds of

cemetery loam have materialized. William suspects she scoops handfuls of them

into her pockets in the afternoons they spend in the cemetery. There is a

steadily growing pile of bird bones beneath her pillow, from sparrows and crows

and wrens and rooks. William has no idea how she identifies them all.

He has seen her

asleep in the bed only once, by chance, when he woke before her. She sleeps

with a blackbird claw beside her, curled on the pillow like a withered vine.

She wakes with

twigs and crumbling leaves in the tangle of her black hair. William’s mother

plucks them from her hair before combing it at the breakfast table. She makes

no remark as to how they might have gotten there. She is too unnerved and

scared to rearrange the crow girl’s bed when she enters the room to sweep it.

But even as

disturbed as she is, William’s mother strokes her hair gently. It is another

effect of the crow girl, the impulse to impart tenderness upon her, as one

might on a lost child. But when William’s father once asked her if she was

lost, she smiled and shook her head.

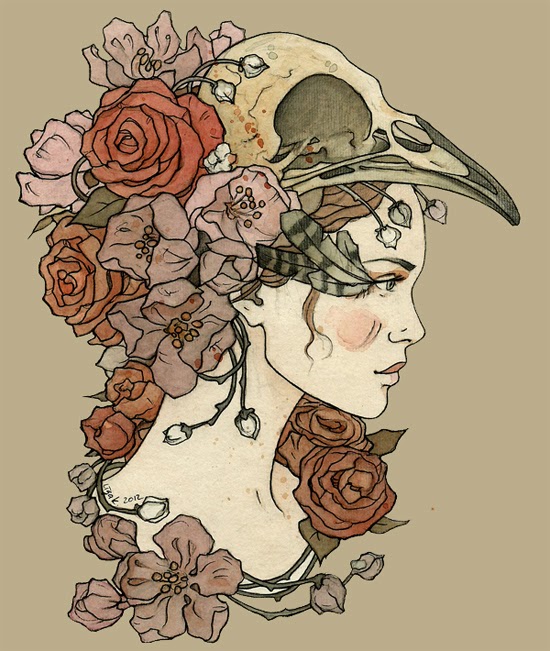

Art by Ludovic Jacqz

Text by Lucie MacAulay